by Natalie Bryant Rizzieri

One summer day, deep in the heart of Queens and in the throes of mothering two young children, I began rummaging through my books on spirituality. I have long been enchanted by the mystics – Hafiz, Teresa of Avila, Rumi, St. John of the Cross, Adelia Prado, and Hildegard von Bingen, to name a few. Even since stumbling away from organized religion and a very conservative strand of evangelical Christianity, I remain drawn to the mystics because of their deep and abiding hunger to experience the divine.

I relate to that hunger. I am driven by it. And I know I am not alone. So many of us who were raised in evangelical Christianity, who were schooled in morality over mysticism, who were taught to trust in scriptures over trust in oneself, who were offered private salvation over collective action and justice, and taught to value doctrine over direct experience, have been left empty-handed and hungry. Many of us have gone searching for a new and even mystical way – one that would not only cease to ostracize the sublunary and denigrate daily life but would also elevate it – along with its nuances, sensuality, ashes, darkness, uncertainty, and silence. Many of us seek a mysticism of belonging as differentiated from inclusivity, which unfortunately still implies that there is an “in” and an “out”.

In my search, and despite a handful of interruptions from a crying toddler who was lying outside my door, I looked through my books, many of which chronicle various mystical and spiritual paths, hoping to find proof that it was possible to maintain a substantial spiritual practice while mothering small children and living in the largest city in the United States. Both were a stretch for me, being an introvert accustomed to spending most of my days alone and as a forest dweller living in New York City for the sake of my husband. I was struggling against the lack of wild and calm spaces within and without.

After leaving organized religion, I had to relearn how to connect with the Mystery. I wanted to know the truth of Jack Spicer’s words in After Lorca when he said, “As things decay, they bring their equivalents into being,” but I was not yet convinced. I needed the equivalent (and maybe even the opposite) of an old, religious, belief-oriented, transcendent connection within a new framework, within a new body, even, and within a new context. I knew how to connect with Mystery in pristine wilderness, in solitude, in beauty, as a hermit, and within organized religion. But none of these avenues were available to me any longer. Could I be so blessed that in the necessity of relinquishing these cherished ways, I could make something new and real?

This day I was feeling particularly desperate. With two children, the tangles of a large city, a marriage, and a job running a non-profit I founded to support abandoned individuals with special needs in Armenia, there was no denying that I was held fast and tethered to the earth by my own gravity, the weight of my family and those I served and loved. This was not at all how I imagined mystics to be. I had bought into and internalized the historical myth that was reiterated time and again that women’s work was less valuable. In Wild Mercy: Living the Fierce and Tender Wisdom of the Female Mystics, Mirabai Starr says that: “Every culture and religious tradition controlled by men has placed higher importance on scriptural study and ritual observance than on feeding babies and cleaning up after them. Women have internalized our own devaluation.” I had done the same. This was not the context in which I had sustained a mystical practice for the years prior. An annual week or two of solitude and study had disappeared entirely with nursing and raising babies. The wilderness was unreachable due to traffic and suburb after suburb. Rituals that I had carefully crafted when childless were impossible with the near constant interruptions. Beauty had to be completely redefined and reclaimed.

A few nights before, we had a family over for dinner that my husband had recently met at the park. My eldest child didn’t like having new people in our home. He wasn’t apt to curb his thoughts for the sake of decorum. I could see his frustration building as the nine of us sat crammed around a small table made for six. Finally, he turned to me, his face red as a coral bead, and said, “I want to take this glass and break it and use the glass to cut these people.” I’ll say it again: my life was not what I imagined a mystic’s life to be.

So, I dug through books and memories, stories and conversations. To my further despair, I came up all but empty handed. In one anthology of notable individuals within the Christian tradition, only three women out of hundreds were even included. Three. Not one of them was a person of color, even though people of color were the original Christian mystics. Not one of them was married or had children. Even in more recent books that weave together mystical voices of women, in particular, and explore divine feminine symbols from various traditions, the examples given are women who were pilgrims and were not mothers or caregivers. Granted, women did not have much choice on either front given their historical context, but that is entirely the problem. At many times during history, it would have been too risky for women to speak out, to gather openly, and to claim her own spiritual authority. As a result, white men in societies that only rarely included women, and especially women with children, have written most of the mystical texts we read today.

I needed a more earthbound and feminist exploration of mysticism written for those of us who have chosen willingly and purposefully to abide primarily in the temporal world, written by a woman with children she desperately loves, written by a woman whose children say things like mine at the dinner table, written by someone surrounded by chaos and the unruly, written by someone who prioritized experience over the construct of belief, written by someone who didn’t want to appropriate another culture’s beloved traditions but who, nonetheless, needed something on which to hang their heart.

I know for certain that I am not the only individual with children filled with an insatiable longing to exist within the heart of the sacred. I see a deep and absorbing hunger in women and men alike to create a unique, fulfilling, and even mystical spiritual path outside of the bounds of organized religion. I hear about it on the playground. I see it in my book club. And most of us don’t want to become hermits (at least not on a typical day). We want to hold down jobs and possibly raise children. We don’t want to be required to give up our identities as women or parents. We don’t want to have to trade our identities in for this longing.

So, I wrote the book I most needed, within an experience of exile from the forest and from the God of my childhood. I wrote as a wife and mother, all of which seemed at first glance to disqualify me from the path of a mystic. I did not want the atypical mystical terrain of these years to be lost. And just as importantly, I did not want to lose the divine in this season of my life. And this was at risk, largely due to the fact that I didn’t have anyone to show me the way and because my life no longer had the structure and space that had previously allowed me to experience the divine.

I had to start over.

I determined then and there to make a mystical path where others may have deemed that impossible and to chronicle my own prosaic (sometimes joyful, sometimes infuriating) existence as that mystical path toward the heart of the divine. I had already left behind the path of organized religion and had to furthermore decide that at least for now I must leave the path of transcendence behind as well. I had to attempt to find the divine in the immanent, in the pleasure of my children’s hands in mine, in the earthbound, in the sounds of a crying toddler. I had to learn to transform what I had assumed was interference into a sacred way – seeing these perceived obstacles as entrances. What I did not know yet was that the question was not how to maintain a spiritual practice in this season but rather how mothering two small children in New York City could actually be my spiritual practice.

I invite you to do the same – to discover that the shape of your unique and muddy life can in fact be your mystical path. I hope that these words will spur you toward your own articulation – that you will create a mosaic with the beautiful and broken pieces of your life. As Alexander Chee says in his essay, ‘How to Unlearn Everything’, “Most of what has survived to us thus far is literature written by white male writers. The last three decades especially have seen a struggle to revive the books we have lost – books by women, people of color, and queer writers – and to then try and write out of that recuperation a new tradition.”

If you are a woman, I invite you to help me craft – through the dailiness of your own life – a robust feminist or archetypally feminine description of mysticism. If you are a man, I invite you to participate in an embodied feminine mysticism and to help craft a profoundly embodied masculine description of mysticism. If you are a person of color or a queer writer, I am searching for your unique (or possibly lost or appropriated) descriptions of mysticism. Let’s reclaim mysticism from the confines of privilege and celebrate the immanent and earthbound. We will learn from one another, as these descriptions emerge through books, conversations, poems and music.

I am confident that there were mystics among those women and men, black and brown and white, who were exiled or oppressed, who prioritized family over education, rootedness over wandering, immanence over transcendence, experience over theology, dark over light, descent over ascent and body over spirit. But we so rarely hear from them in this context and the voices that we do hear are diametrically opposed to the shape of my life, to motherhood, though not, as I would discover, necessarily to mysticism. And even while I have no doubt that mystics have existed in each and every corner, category and confine, unchronicled mysticism does not serve those of us who are hungry for insight today or who may live in the periphery of the historical texts. Being a white woman, I can only help to remedy the dearth of public female voices who are in long-term intimate relationships, who have children and who live in the city. An archetypally feminine perspective of the divine is largely lost when we tell the story of history and it is our work to reclaim that through the fervor of articulation and practice. My only hope is that the very fact that a prosaic mysticism was left unwritten is an invitation to find our own particular way toward the heart of the divine. And one that will be always unfolding. To quote Alexander Chee again, we are “writing out of that recuperation a new tradition.” Our liberation is at stake, whether it be liberation from patriarchy, racism, oppression, dogma or an exclusively transcendent spiritual vision.

I have known the glory and beauty of rising above. In one long season of my life, I would even say that it saved me. But for those of us who are no longer untethered, we need a mysticism that can stalk the wild shores of our daily lives. At the very least, we need a mysticism that is saturated in immanence and transcendence both. To combat hopelessness and a monochromatic schema, we need our eyes opened wide to our own unique daily dance with the divine, however chaotic, mundane, mulberry-stained and understated it may be. My book, Muddy Mysticism, is my search for an awareness that the divine lives in the streets, in the throes of family life, in my particular day-to-day. This is my articulation of a sub-lunary and muddy mysticism that is equally available to men and women alike but remains intertwined and earthy, sense-oriented and variable, and interdependent with all beings and all things.

This is a mysticism for those who love the world or want to love it more. It does not require a degree or a certain disposition, a religion or a church. It is not in creeds but in the prayers of the body as we move through the day. It is in the common moments we share – the collective experience of a train ride, kneeling to pick up puzzle pieces, the way sycamore branches click together like ice cubes in a glass.

I do not want someone to tell me what the experience of the divine is or is not. And I do not want to tell you, either. But I want it. I scour my days for it and hope to come forth baptized both by what is and what is not. Perhaps we do not have to find God as much as know God in our own hunger, in the reciprocity between nature and our bodies. If God is, then God is with us. All of us. We may not always know it. But we may spend our lives trying. And whatever happens or doesn’t, it is still worth trying.

Find out more:

Find out more:

Natalie Bryant Rizzieri is a poet, writer, activist, mother and mystic. Her poetry is published in journals such as Denver Quarterly, Pleaides, Terrain.org, and Crab Orchard Review. She is the founder and director of Friends of Warm Hearth, a movement of forever homes for abandoned Armenians with special needs. She lives in Flagstaff, Arizona with her family.

Bookshelf

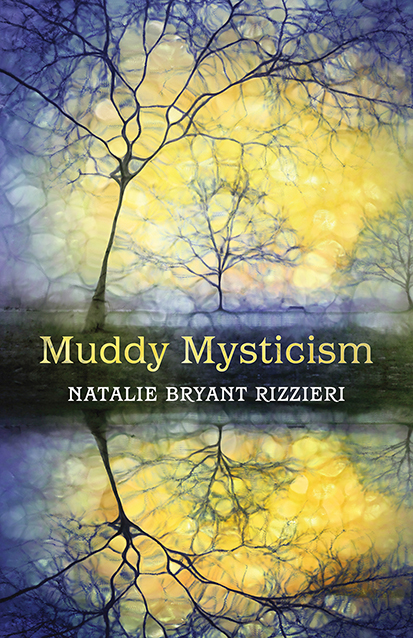

Muddy Mysticism: The Sacred Tethers of Body, Earth and Everyday by Natalie Bryant Rizzieri, published by Womancraft Publishing, illustrated paperback (254 pages).

Cart is empty

Cart is empty