By Jonathan Stedall

I wonder what sort of a person Winnie the Pooh would be like if he reincarnated as a human being. Would he still write poetry, and still be fond of honey? I suspect he wouldn’t be slim! And would Piglet be someone who continued to see danger round every corner, and Eeyore be as gloomy as ever? And what about Tigger? Maybe his Indian roots would surface in the form of an interest in karma?

These are some of the playful questions I’ve been living with over the past year, while writing a story in which A.A.Milne’s much loved creations do indeed find themselves alive and well, and living in the village of Hartfield on the edge of their old stamping ground, the Ashdown Forest. Yet none of them have the slightest awareness of their similarities to Milne’s original creations – not even Sheila, an Australian single Mum with a somewhat obsessive devotion to her small son, Joey.

In my story their beloved forest is under threat from a proposed bypass. To oppose the scheme an Action group is formed under the leadership of the formidable Bunny, a much-respected citizen of Hartfield, with a reputation for getting things done. Her main ally is Bertie, a dreamer and an idealist, with a deep interest in what he calls ‘a bigger picture’. And yes, he does write poetry, keep bees, and is friends with everyone.

As the saga unfolds, a distinguished member of Bunny’s Group, known to everyone as the Professor, is suddenly faced with a serious illness. The situation leads to all sorts of discussions about mortality, with Bertie trying to communicate his strong sense that our existence continues beyond death. The Professor has no such faith.

‘I don’t want people bringing me grapes and books about the afterlife’, is his initial response to Bertie’s offer of help.

In fact their relationship has always been overshadowed by the Professor’s irritation at Bertie’s belief in all sorts of ‘mumbo jumbo’, and by his friend’s concern at our increasing addiction to technology. Only recently this scholarly and somewhat reclusive figure – who no longer lives in a tree, but in a proper house called The Cedars – has taken a certain pleasure in showing Bertie an article about some scientists in the Netherlands who are in the process of developing bee-like drones. These gadgets would be capable of pollinating plants in preparation for the day when real-life insects will have largely died out owing to the excessive use of pesticides.

But attitudes do gradually change, and all the characters – even the Professor – start to reveal more thoughtful aspects to their natures as they begin to do battle with the unseen giant that threatens to invade their forest, as well as to accept and appreciate each other’s eccentricities. As a result even Bertie’s timid friend, Peggy, begins to find the courage to talk about her past and the roots of her nervousness. Meanwhile Sheila’s new lodger – an actor affectionately known as Bouncer, whose grandfather was a famous Bengali poet – brings his enthusiasm and humour to the challenge they face.

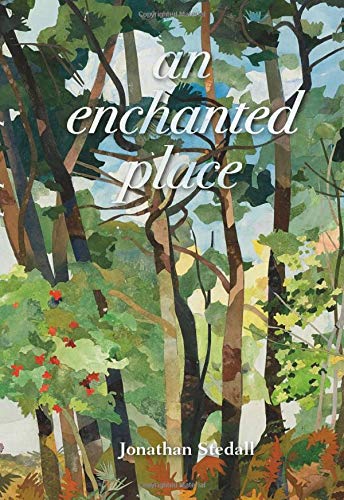

The title of my story – ‘An Enchanted Place’ – comes from some lines that A.A.Milne wrote at the conclusion of ‘The House at Pooh Corner’:

‘Come on!’

‘Where?’ said Pooh.

‘Anywhere’, said Christopher Robin.

So they went off together. But wherever they go, and whatever happens to them on the way, in that enchanted place on top of the Forest a little boy and his Bear will always be playing.

I’ve chosen to write about this colourful group of people not only for the fun of imagining Owl as a university professor, and Tigger as a gay actor who’s afraid of wasps, but above all to celebrate my experience that people – including so-called ordinary people – are a lot wiser than appears on the surface. It may take some sort of crisis to wake them up, and in my story the threat of a bypass being built across what one cynical counsellor called ‘unused space’ does just that.

Another of my themes is the way that very different characters can work together fruitfully, just as they do in Milne’s original stories. There are, of course, clashes, but it is often those very differences that enable things to happen that no one individual could achieve on their own. However, it is the Professor’s illness that creates the biggest shift in the minds of those who know him.

‘We take so much for granted’, says a distressed Bunny, ‘not least our health and the health of our friends ….. So much for granted’, she repeats wistfully. ‘Tomorrow’s sunrise, the postman, church bells on Sunday, water from the tap; above all the people we care about.’

The Professor, on the other hand, is determined to take a philosophical approach to the news from his doctor – at least initially.

‘I was told recently that my toaster wasn’t worth repairing’, he says with just the hint of a smile. ‘I’ve had it twenty years or more. I’m not going to argue.’

‘You’re a little more complicated than a toaster’, says Bertie.

‘Thanks for the compliment, my friend. But I’m not really. Parts wear out. Some are not replaceable. An obsolete model is what I am.’

The Professor isn’t the only person whom Bertie tries to comfort.

‘As long as we think of life only in physical terms and as finite’, he says to his busy, but tearful friend Bunny, ‘then death is naturally forbidding and something to be feared. But if death is not an end, but instead an interval, just as sleep is – a sleep from which we wake each morning – then it is something to be welcomed, not dreaded. We need that pause, just as we need each night.’

Life and death, laughter and tears – it all unfolds in this ‘enchanted place’, as it does in every community. What I hope also emerges from my story is the sense that Bertie’s ‘bigger picture’ is a reality. It may be largely unseen, but it is deeply felt by everyone who has the urge to keep asking those difficult questions about life and its meaning. In a conversation with Bouncer about his bees (quoted below), Bertie tells him how they have helped him to understand the notion of hierarchy. The hive is not, as some people think, some sort of gulag imprisoning its individual members, with the queen in charge, but rather one single entity in which you see cooperation on a magnificent scale.

‘Like our bodies’, suggests Bouncer; ‘the heart, our lungs, the liver – they all have their individual roles so that we can stay alive.‘

‘You’re absolutely right,’ responds Bertie. ‘Each organ is absolutely necessary; therefore there is no one organ more important than the other.’

After a pause in which they both felt the need to digest what they had been discussing, and while they watched the sun finally emerge from the early morning mist, Bertie spoke again.

‘I’ve sometimes thought that in the past we spent too much time looking up at the stars and imagining other worlds and gods, and not paying enough attention to what was beneath our feet. Now we do the opposite, but maybe we’ll gradually discover that the two belong together.’

‘You mean that the universe is one great beehive’, laughed Bouncer, ‘in which everyone and everything plays an essential part – you, me, wasps and angels. It’s a wonderful idea.’

One other idea that emerges from my story is that alongside our intelligence we will need to foster and to trust our imaginations and intuitions to a far greater degree, if we are truly to understand the great mysteries of existence. It’s an idea that is subtly hinted at in one of Milne’s stories.

‘Rabbit’s clever’, said Pooh thoughtfully.’Yes, said Piglet, ‘ Rabbit’s clever.’

‘And he has a brain.’

‘Yes,’ said Piglet, ‘Rabbit has brain.’

There was a long silence.

‘I suppose,’ said Pooh, ‘that that’s why he never understands anything.’

Find out more:

Jonathan Stedall is an award-winning documentary film director who worked at the BBC for over twenty-five years. He has made biographies of Tolstoy, Gandhi, Carl Jung and Rudolf Steiner, and worked on films with John Betjeman, Alan Bennett, Mark Tully, Malcolm Muggeridge, Cecil Collins, and Laurens van der Post. His autobiography ‘Where on Earth is Heaven?’ was published in 2009. Karen Armstrong wrote: ‘A real quest, with outward work perfectly integrated with an inner search’; and John Cleese called it ‘the most annoying book I’ve ever read, as the author seems to have had a more interesting life than I’ve had.’

Following the death of his wife in 2014, Jonathan published ’No Shore Too Far’ – a collection of poems on the theme of death, bereavement and hope.

‘An Enchanted Place’ is his first work of fiction. The critic and satirist Craig Brown has written: ‘Jonathan Stedall has directed some of our most enjoyable documentaries, and now has turned his hands to something as lively, original and thoughtful in prose.’

‘An Enchanted Place’ is published by Hawthorn Press @£14.99. ISBN: 978-1-912480-46-3

Cart is empty

Cart is empty