On the back cover of the Penguin Classics edition of Paradise Lost we read, “An endless moral maze, introducing literature’s first Romantic, Satan…”

This quote by critic John Carey is rather pertinent, for the author of the book, John Milton (1608-1674), was one of the most pious of men. Yet he went beyond this when writing. That is, as a writer spirited away to the lands of artistic freedom in a creative trance, Milton portrayed the glorified ‘bad guy’ of the story, Lucifer, as a being to whom we can all relate, somehow worthy of our open-minded interest. This was indeed ‘sympathy for the Devil’, three hundred years before the Rolling Stones made the phrase memorable.

In this ground-breaking literary vision, Lucifer’s role is that of a ‘spiritual freedom-fighter’. He is not merely plain evil but can be seen as a symbol of spirituality, in the sense that Rudolf Steiner (1861-1925) spoke of ‘the Luciferian influence’ as an integral part of Man’s efforts to find spiritual wholeness. Put simply, we need to be free, independent and self-reliant, and Lucifer gloriously symbolises this. He breaks down the old, tribal moulds of Mankind and shows us a way that enables a life of innumerable possibilities.

Now, many would say that a balance to such personal freedom is also needed, so Steiner offers us the figure of Ahriman, who represents obedience to law and tradition, whilst Luciferian freedom-and-independence are transformed by Christ into compassion and spiritual love. Few spiritual thinkers have been able to avoid such balance and Lucifer’s role as freedom-fighter is often repressed, neglected or forgotten. Therefore Paradise Lost is an important starting point in showing us a very different way of approaching the spiritual path.

This epic poem tells of a war in Heaven resulting in the rebellious angels, led by Lucifer, being thrown out. They then try to get back at God and assert their authority by tempting Man into sin. The whole structure of the story itself may be a little contrived: basically, it is about getting Eve to eat that apple from the Tree of Knowledge. But along the way Milton says and portrays a great deal about devils and angels, God and primordial Man, as well as reviewing Man’s moral history among other telling passages, all in an iambic pentameter rhythm.

No-one writes epic poems like this anymore, not in this form and on this scale, yet Milton’s magnum opus has had a lasting impact, especially in our thinking about the figure of Lucifer. One man who saw very early the heroic-tragic character of this antihero was William Blake, British poet and mystic (1757-1827). He loved Milton, to the extent that, for example, he became the main character in Blake’s own eponymous epic poem, Milton, also illustrated by the author himself. One illustration even shows how the author gets his inspiration from a star that emanates from Milton, falling down and being absorbed into Blake’s foot. This might seem a little far-fetched to us but then Blake’s art was like no other.

To be sure, Blake also uses his poem to ‘correct’ certain things that he thought Milton had got wrong. Nevertheless, this romantic was deeply impressed by the earlier work’s descriptions of God, angels and Man, and saw these as the way ahead for art. This was to be Blake’s way of expressing his visions, alongside the influence of the Book of Revelations with its cosmic doom, angels and demons and cast of millions.

Indeed, Blake saw what we today see as obvious, that Lucifer is actually the hero – or is it antihero? – of Paradise Lost. In The Marriage between Heaven and Hell (1794), Blake suggests that Milton was restrained when depicting what is generally accepted as ‘good’ but far more free when depicting supposed ‘evil’. Why was that?

“The reason Milton wrote in fetters when he wrote of Angels & God, and at liberty when of Devils, is because he was a true Poet and of the Devil’s party without knowing it.”

Blake went even further, providing illustrations for an edition of Paradise Lost, in which Lucifer Arousing the Rebel Angels is a prime example. Here we see Lucifer as an athletic youth, curly-haired and charming, with an expression bordering between melancholy, wrath and sadness. This is the romantic hero in his most glorified form: he is more than human yet at the same time recognisable to us – certainly more so than a heavenly angel who, true to his nature, must be more distant, equanimous and unmoved.

For his part, Blake was himself a kind of ‘New Age’ pioneer and he even used the phrase itself in the preface to Milton. Conceptually he also held opinions such as ‘anti-God’ and being in favour of creativity and free-love. He opposed all forms of law – natural law, juridical law and Biblical law, such as the Ten Commandments. Rather than being restrained by obeying laws, man should be free, a creative individual living entirely in the now, so to speak. (Contrast this with John Locke’s adage a century before, ‘Where there is no law, there is no freedom.’)

Blake belongs to Romanticism and this era had a flair for divine antiheroes. Shelley and Goethe, for example, both wrote about the ancient Greek god Prometheus, an antique Lucifer, as an outcast and a friend of humanity. According to some myths, he even created Man. For example, certain Gnostic scriptures say that their equivalent of Lucifer, one Yaldabaoth, created Man. God then adopted him and gave him eternal life by giving him a soul. He appears in the Apocryphon of John (c. AD 120–180) as a demiurge and chief of seven archons (rulers) where he boasts, “I am God and there is no other!”

Prometheus battles with Zeus, Lucifer battles with God… it is the eternal story of cosmic rebellion in a form we can understand. The Romantic craze for Prometheus can probably be seen as a kind of Luciferianism in disguise: it wouldn’t have been easy to portray Lucifer as not really the enemy of Mankind in a work of art in those days, the early 1800s, when Christianity still held great power over the cultural life of western Europe.

However, one work of this era does openly features Lucifer, not as the downright enemy of man but, instead, playing a glorified, if dubious, role. This is Byron’s Cain (1821). Like Blake, Byron was impressed and influenced by Paradise Lost and in particular its portrayal of Lucifer, who plays a significant part in Byron’s drama, featuring in the first two thirds of it. Fittingly, when he first appears he is described as, “a shape like to the angels, yet of a sterner and a sadder aspect.” The plot focuses on Cain, the son of Adam and Eve and a primordial rebel who, following Lucifer’s directions, turns his back on God. The play can be seen as an atheist preachment of freedom and, especially, a freedom from the perceived tyranny of God (in the form of Church).

You could say that Byron’s version of this antihero offers a kind of ‘dark enlightenment’ compared to Milton’s worldview: the latter spoke of spiritual development under God’s aegis, whereas Byron saw only death and decay. His outlook was not at all spiritual, even though this and other of his plays such as Manfred do have some mythopoeic qualities.

The image of Lucifer throughout history has been very varied. The French artist Gustav Doré’s illustrations to Paradise Lost (1873) are more academic, more restrained than Blake’s, though it is also true they do not have that certain ugliness of some of Blake’s art. We can relate better to Doré and many of his illustrations have become classics too, like Lucifer Hurled from the Heavens. His art also seems to have inspired French symbolist Odilon Redon (1840-1916), such as the painting The Fallen Angel Spreads his Dark Wings: this image is tranquil and naïve, in the best artistic sense.

Moving on to the present day, mention must be made of a modern classic picture, that of Patrick Woodroffe’s cover for Judas Priest’s 1976 album Sad Wings of Destiny. With artistic roots in Blake’s curly-haired and handsome Lucifer, we see a being with the body of a Greek god and avian, feathery wings (influenced by Doré). Here, this elevated being has now been referred to Hell, where there are flames and burning sulphur and a heat-haze around him. This fully-fledged Greek anatomy works well here. Whilst Blake disowned Greek art, some of his work certainly lacked the beauty and sublimity through and through of Woodroffe’s cover, Pop Art though it may be.

Just five years later, we find another minor cultural classic on a similar theme, in Michael Moorcock’s novel The War Hound and the World’s Pain. Here, an army captain of the Thirty Years’ War leaves his service after the sack of Magdeburg in 1631, tired of the slaughter and evil-doing of his times. This Captain Graf Ulrich von Bek is no saint, though, rather a dark knight of the era, yet he still finds that he needs some vacation of the spiritual kind. He ends up in an enchanted, unusually quiet forest, home to a castle whose unearthly master is Lucifer. This Prince of Supposed Evil is described as being more beautiful than any mortal, a personage of intense and majestic, even ethereal beauty.

The Lucifer we meet in this novel is a memorable acquaintance, perhaps not entirely original per se yet Moorcock manages to make his scenario perfectly relevant to the modern reader. For instance, Lucifer shows von Bek Hell but it is a place where the lost souls stumble about, not in torment, but in a psychological darkness. Each soul is busy with ‘being himself’ and, in so doing, they all end up being similar to one other. This is indeed Hell! That this depiction might have been inspired by William Beckford’s Vathek (1781) doesn’t diminish its impact at all.

Why, then, has Lucifer sent for the Captain (since he certainly didn’t arrive here by chance)? It is to ask him to find the Holy Grail so that, with possession of it, Lucifer can be reconciled with God, his father. This redemption will be the ultimate cure for the world’s pain. von Bek agrees to fulfil the mission – does he have a choice? – and sets off on a quest through spectral and numinous landscapes, both of our world and of a parallel world, in ‘the Multiverse’ (introduced in other Moorcock stories).

Without revealing the ending, we can say that the denouement is quietly and satisfactorily spiritual, given that Moorcock isn’t a typically spiritual author. Our hero finds himself affirming ‘lux aeterna’, ending up in spiritual lands rather than, as he was wont to do in his earlier life, in self-righteously nihilist lands.

This is the beautiful, conceptual bookend to Milton’s experience. Milton sought to portray the divine worldview, which resulted in giving us a hellish antihero. Moorcock, for his part an atheist and never one to preach of celestial quiet or of a cosmic understanding flowing down upon the hero, nevertheless gives us just this at the end of his novel.

Indeed, Lucifer can be seen as a kind of complement to many spiritual attitudes. In art and literature, as we have seen, he is one of the prime symbols of freedom. And with the help of an approach such as Steiner’s we may be able to develop a more fully rounded spiritual creed than simply saying, “God is love…” A little rebellion is also needed, for the mindful seeker. Whether or not one sees oneself as a rebel, freedom of the individual is an essential concept to the Western mind despite traditional creeds such as Christianity rarely acknowledging any need for spiritual freedom.

Even in eastern philosophies there is śānti (peace) and śūnyatā (emptiness) although many Western seekers find this approach rather frustrating, a little lacking. We are steeped in the need for freedom, and seeking it has shaped us, whatever some official, traditional creeds have tried to teach or impose. We want to be personally active and involved, the heroic quest is in our DNA, in our blood.

Freedom needs to be elevated to the role of spiritual necessity – and maybe Lucifer as antihero can help us with this.

MEET THE AUTHOR

MEET THE AUTHOR

Lennart Svensson was born in Sweden in 1965, in the inner part of Norrland, in the middle of the thousand-mile taiga. His grandmother told him stories of elven creatures of the woods and TV told him of future vistas.

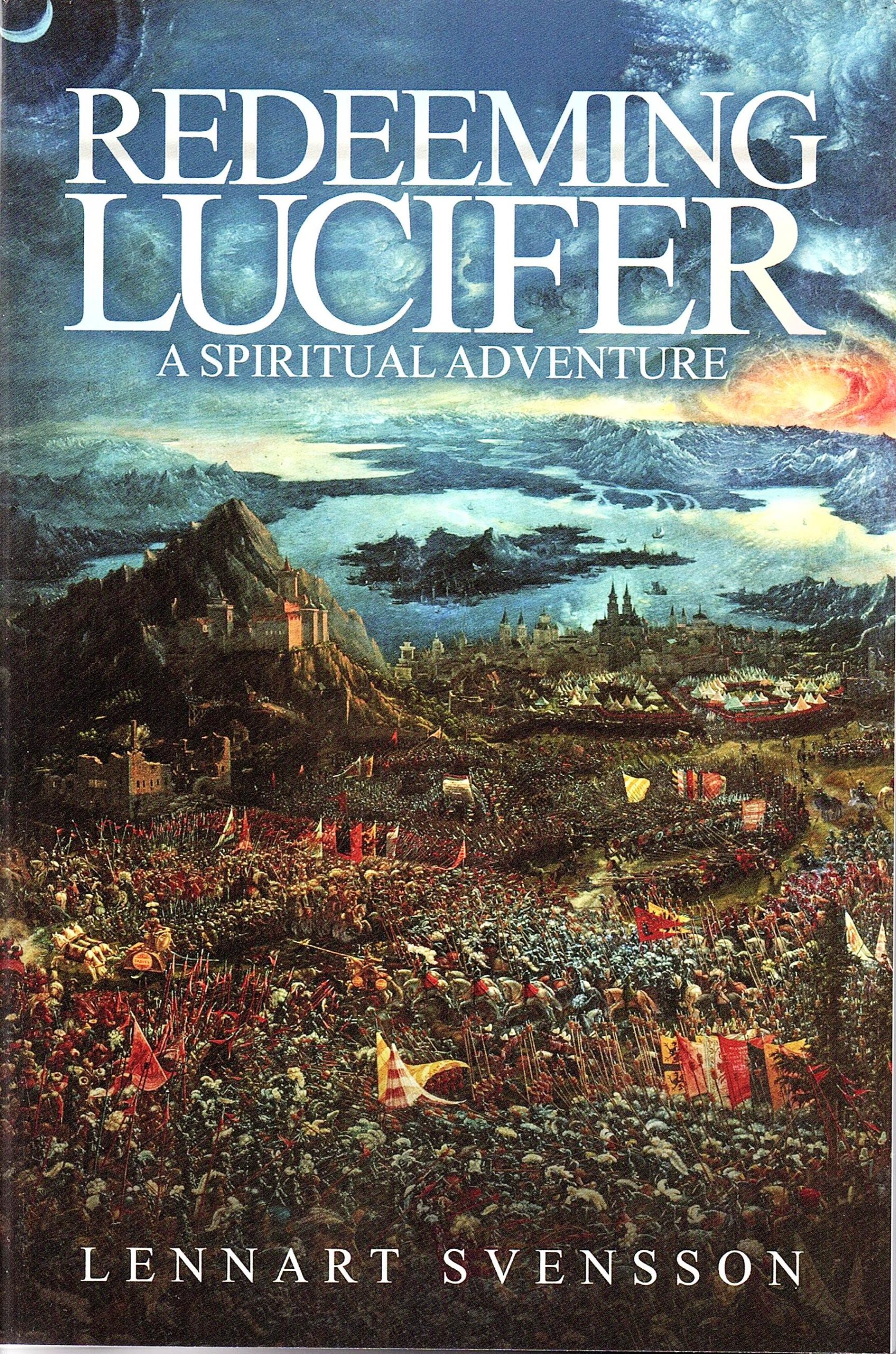

After receiving a BA in Classics Indology Svensson started writing. After publishing some works in his native tongue he switched to writing in English, resulting in biographies of Jünger and Wagner, the conceptual essays Borderline and Actionism, and the novel Redeeming Lucifer.

Svensson is currently planning more essays and novels, predominantly in English. He has a predilection for science fiction and fantasy, his first literary loves.

ABOUT THE BOOK

Lennart Svensson’s debut novel in English is Redeeming Lucifer, a page-turning spiritual adventure in the finest traditions of legendary quests. It blends esotericism, imagination and acutely observed historical fact as our heroes journey through parallel, mystical worlds with the epic task of healing the world of its ills – provided they survive the ultimate cosmic battle of Gnipaheden…

Cart is empty

Cart is empty